Posted by Imperial Harvest on 12 May 2023

Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins

The Chinese calendar holds a compelling role in Chinese society, guiding holiday traditions while contributing to the understanding of Chinese metaphysics and Imperial Feng Shui.

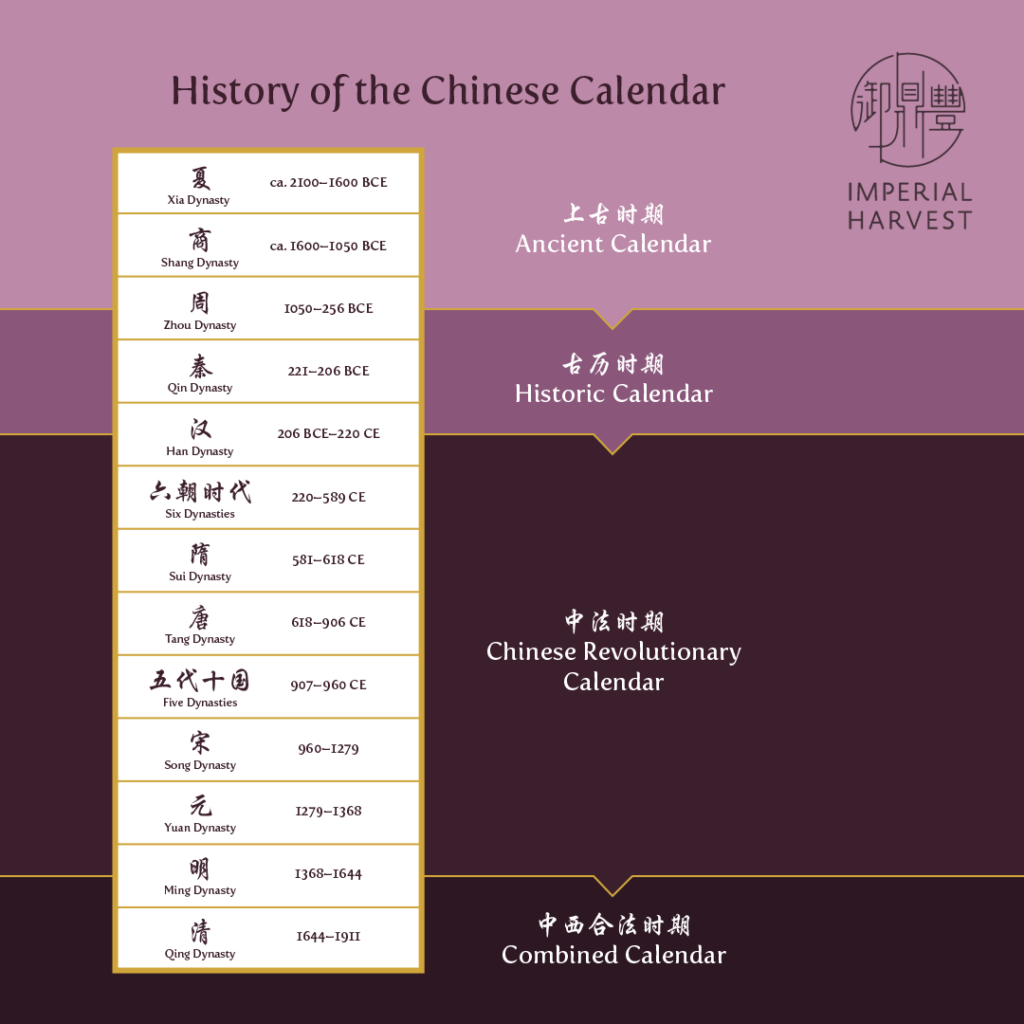

In our previous article, we discussed the origins and developmental history of early Chinese calendar calculation systems from the Ancient Calendar period (上古时期), which formed from the Xia, Shang and early Zhou dynasties between 2070 and 771 BC. Then, we delved into the Historic Calendar period (古历时期), dating back to the Warring States period, the Qin and Han dynasties between 476 BC and 220 AD in our exploration of the historical background of the Chinese calendar.

In this article, we will explore the development of the Chinese calendar during the Chinese Revolutionary Calendar period (中法时期) and the Combined Calendar period (中西合法时期). These developments shaped the modern Chinese calendar, refined through meticulous observation and research of astronomical phenomena over centuries.

Chinese Revolutionary Calendar (中法时期)

Following the Historic Calendar period, the Chinese Revolutionary period encompassed the calendar’s developmental history during the Han and Ming dynasties between 202 BC and 1644 AD. This period marked the Taichu Calendar reformation by Emperor Wu of Han at the start of the Han dynasty.

Between the Qin and Early Han dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han (汉武帝) noticed discrepancies in the then-established Zhuān Xū Calendar. Taking into account advice from court officials, the emperor appointed Deng Ping (邓平), an astronomer, to compile a new calendar that used the 81 Rule (八十一分律历). This rule calculated that a month was equal to 29 and 43/81 days — resulting in the emergence of the “81-point law calendar”, otherwise known as the Tai Chu Calendar.

In comparison with previous calendars, the Tai Chu Calendar improved upon established theories on astronomy and resulted in more accurate observation of the stars’ movements. The use of the 81 Rule in the Tai Chu Calendar recorded both solar and lunar eclipses, establishing foundation sets of data for predicting future eclipse events.

The 81 Rule in calendar calculation systems influenced the way that the four seasons were calculated. Luoxia Hong (落下闳), a Chinese astronomer during the Western Han Dynasty, made improvements to the Qin Calendar which used October as the beginning of the year. Instead, he determined that the first day of the first month was the beginning of the year, and the end of December was designated the end of the year. The Tai Chu Calendar coincides closely with the cycle of the four seasons.

The introduction of the Three System Calendar (三统历)

During the Han dynasty, Liu Xin (刘歆), a mathematician and astronomer, proposed adjustments to Deng Ping’s Tai Chu Calendar. He enhanced Deng Ping’s 81 Rule calculation method by incorporating additional astronomy theories, research, and observations. These improvements were compiled in the “Book of the Three System Calendar”《三统历谱》, leading to the establishment of the Three System Calendar (三统历).

The “Book of the Three System Calendar” is renowned as one of the most comprehensive texts on Chinese astronomy. It covers theories related to calendar creation, solar terms, astronomical events, and the influence of the movements of the Five Stars (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) on calendar calculations. The knowledge presented in this text continues to be employed in the modern Astronomical Calendar (天文年历) and is internationally recognised as a model for developing contemporary astronomical calendars.

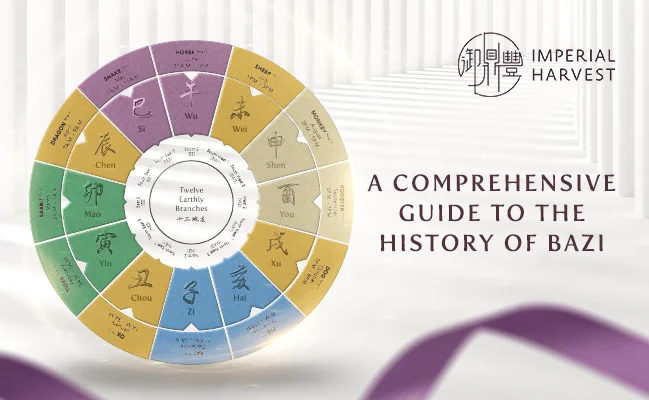

The calculative methods of the Three System Calendar were synchronised with the sexagenary calendar system, which documented the 60-year calendar cycle based on the combinations of the Ten Heavenly Stems (天干) and Twelve Earthly Branches (地支). This calculation method followed a predictable pattern over a 180-year timeline, earning it the name Three System Calendar. Despite its accuracy and comprehensiveness, the usage of this calendar system ceased around 84 AD, approximately 80 years after its publication.

During the Northern and Southern dynasties, Emperor Wen of Song (宋文帝) introduced a new calendar system as part of his political reforms. The court official and astronomer, He Tian Cheng (何天承), compiled this calendar, known as the Yuan Jia Calendar (元嘉历). Notably, the Yuan Jia Calendar incorporated the use of the 5 Stars in its calculations, resulting in enhanced accuracy for future predictions.

The Introduction of the Twelve Qi Calendar (十二气历)

By the Song dynasty (960 to 1279 AD), there were a total of 18 calendar calculation methods in use. During this time, Shen Kuo (沈括), an eminent scientist and statesman, was troubled by the mediocre quality of existing calendar calculation methods. Keeping up with the prevailing flourishing astronomical research, he proposed a revolutionary change in calendar usage, introducing the Twelve Qi Calendar (十二气历). This calendar matched months to 12 main solar terms which were designated as the first solar terms of each month — Lichun, Jingzhe, Qingming, Lixia, Mangzhong, Xiaoshu, Liqiu, Bailu, Hanlu, Lidong, Daxue, Xiaohan. Each major solar term coincides with the 12 lunar months designated by the 12 Earthly Branches.

| Earthly Branch (地支) | Solar Term (Chinese) | English Name | Approximate Gregorian Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 寅 (Yin) | 立春 (lì chūn) | Start of Spring | February 4th |

| 卯 (Mao) | 惊蛰 (jīng zhé) | Waking of Insects | March 6th |

| 辰 (Chen) | 清明 (qīng míng) | Clear and Bright | April 5th |

| 巳 (Si) | 立夏 (lì xià) | Start of Summer | May 5th |

| 午 (Wu) | 芒种 (máng zhòng) | Grain in Ear | June 6th |

| 未 (Wei) | 小暑 (xiǎo shǔ) | Lesser Heat | July 7th |

| 申 (Shen) | 立秋 (lì qiū) | Start of Autumn | August 8th |

| 酉 (You) | 白露 (bái lù) | White Dew | September 8th |

| 戌 (Xu) | 寒露 (hán lù) | Cold Dew | October 8th |

| 亥 (Hai) | 立冬 (lì dōng) | Start of Winter | November 7th |

| 子 (Zi) | 大雪 (dà xuě) | Great Snow | December 7th |

| 丑 (Chou) | 小寒 (xiǎo hán) | Lesser Cold | January 6th |

Table: Illustration of the 12 main solar terms in the Twelve Qi Calendar (十二气历)

This reform addressed discrepancies within the 24 solar terms. The Twelve Qi calendar detailed the start, peak, and end of each season. It synchronised the 12 solar terms with the months. This alignment led to improved agricultural productivity and higher yields. Farmers benefitted from the intuitive calendar. Eventually, the Twelve Qi Calendar became harmonised with the modern Gregorian calendar.

Combined Calendar (中西合法时期)

The Combined Calendar marked the transition from the Ming to the early Qing dynasty, integrating Western scientific methods and concepts brought by Jesuit missionaries. This period witnessed the development of calendars that blended Chinese methods and terminology with Western scientific concepts.

The end of the Ming Dynasty and the start of the Qing Dynasty saw significant developments in calendar calculation and astronomy studies in China. Wang Xishan (王锡阐), an astronomer, almanac maker, and mathematician developed cosmological viewpoints based on scientific breakthroughs in Western astronomy and mathematics.

Combining existing Chinese research with Western concepts of astronomy and science, Wang Xi Shan made discoveries that improved the precision and accuracy of aggregating solar terms and the positioning of the 5 Stars. His research resulted in the Xiao An Calendar (晓庵历), an undoubtedly advanced calendar calculation method. However, this calendar was never implemented due in part to Wang Xishan’s civilian status, and the Qing dynastic parties’ differing political opinions.

Instead, the early Qing dynastic court implemented the Time Regulated Calendar (时宪历). This method was similar to Wang Xi Shan’s Xiao An Calendar, drawing from the Julian and Gregorian calendar calculation methods. The Time Regulated Calendar adopts the calculation methods introduced with the Xia Calendar but was revised with calculation methods learnt from Western research.

The Time Regulated Calendar survived political change and the succession of emperors, although it was replaced for a period of roughly 180 years during Emperor Qian Long’s time. During his reign, the prevailing calendar system had adopted Isaac Newton’s Theory of the Moon’s motion — which was used for the purposes of eclipse prediction. To this day, this calendar continues to be in use and is referred to as the Chinese Traditional Calendar.

Significance of the Chinese Calendar in Imperial Feng Shui

The development of the Chinese calendar forms the foundation for our understanding of Chinese metaphysics. Concepts of astronomy explored and developed in tandem with calendar research heavily influenced important concepts and practices of Imperial Feng Shui.

Bazi (八字)

The importance of the Chinese calendar to the practice of Bazi is detailed in its very purpose, which focuses on the characteristics around an individual’s birth year, month, date and hour of birth. These factors are aggregated to real solar time and used to interpret their destiny, personality, relationships, interactions with their environment, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and risks.

Each individual Bazi chart comprises the Ten Heavenly Stems and Twelve Earthly Branches, structured according to the Four Pillars (四柱命理):

- The Year Pillar (年柱): refers to the lunisolar year, starting from Lichun (立春) or the start of Spring

- The Month Pillar (月柱): refers to each of the twelve months in the year

- The Day Pillar (日柱): refers to any of the 365 days of the calendar

- The Hour Pillar (时柱): refers to the 12 bi-hourly segments of each day, according to the individual’s time of birth

The 10 Heavenly Stems correspond to elements and Yin-Yang polarity, while the 12 Earthly Branches represent zodiac signs, elements, bi-hourly timings, and seasonal and directional systems.

The importance of understanding Bazi

Understanding a Bazi chart is crucial in the pursuit of breakthrough successes. Bazi helps sales professionals understand their sales personality, assisting in developing winning marketing strategies to advance their products, services and businesses. It also helps them understand the profiles and personalities of their clients, and identify those who share a strong working chemistry.

For career professionals, understanding Bazi fosters the development of professional relationships with colleagues and superiors. It also helps to discern the steps towards achieving consistent career progress and stellar professional results.

With Bazi, entrepreneurs are able to identify potential industry partners and the feasibility of business ideas. As Bazi sheds light on an individual’s luck trends, it facilitates identifying the optimal timing to launch a business.

Auspicious Date Selection

To ensure smooth progress and favourable outcomes in both personal and professional endeavours, auspicious date selection is vital when conducting important business, events and occasions. The understanding of the Chinese calendar underpins the practice of auspicious date selection, which focuses on selecting the most suitable moment to conduct important activities. This careful planning facilitates the success of noteworthy activities such as groundbreaking ceremonies, moving houses, conducting renovations, activation of auspicious stars and deactivation of inauspicious stars.

Bazi is often practised simultaneously with auspicious date selections, with Bazi’s dynamics and the methods and principles of the Xia calendar making up a large component of the latter. While the Chinese calendar identifies auspicious and inauspicious dates for events, the personalisation of a Bazi chart allows an experienced Imperial Feng Shui practitioner to discern the elemental and metaphysical capabilities of a person. In turn, this allows for the recommendation of specific dates that may be more suitable and beneficial.

Now that we have discussed the historied background behind the Chinese calendar throughout ancient Chinese history, Imperial Harvest’s blessed readers have a better appreciation of how it has attained its current status.

In the next article in this series, Master David will share his insights into how the development trajectory of the Chinese calendar has culminated in the refinement of the ultimate art and science of auspicious date selection – the Xuan Kong Da Gua Date Selection method.

Imperial Harvest’s expert consultants are always on hand to guide you on your journey and provide you with insights to help you realise your fullest potential. Book a complimentary consultation today or contact us at +65 92301640.

We are located at

For prospective clients:Imperial Harvest402 Orchard Road

Delfi Orchard #02-07/08

Singapore 238876 For existing clients:Imperial Harvest Prestige

402 Orchard Road

Delfi Orchard #03-24/25

Singapore 238876

Most Read Articles

Get to read our life changing articles and get inspired.

A Comprehensive Guide to the History of Bazi (八字)

Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins Bazi (八字) is often mistakenly assumed as the Chinese counterpart of western Astrology. The similarities between both systems lie in their utilisation of birth dates and time in their calculations, and the ability to be read from a tabulated chart. Where Astrology may take into account the positions of different […]

Beginner’s Guide to Bazi Reading

Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins Bazi (八字), or the Four Pillars of Destiny, is a multidisciplinary study in Imperial Feng Shui. It encompasses a well-developed set of metaphysical principles based on planetary influences, the duality of Yin and Yang, and the Five Elements. What is a Bazi Reading? Bazi is an intricate discipline within Imperial […]

Chinese New Year 2026: Auspicious Dates and Calendar

Imperial Feng Shui Date Selection by Grand Master David Goh In Chinese metaphysics, success is not determined by effort alone — timing is equally decisive. 2026 marks the Year of the Crimson Horse, a year characterised by strong Fire energy, speed, visibility, and decisive movement. It is a year that rewards bold action and leadership, […]