Posted by Imperial Harvest on 05 May 2023

Estimated Reading Time: 4 mins

The Chinese calendar, also known as the lunar or Xia calendar (夏历) is an important system used in the calculation of dates and guidance of holiday traditions in Chinese culture. While the Gregorian calendar has been accepted and is widely used in modern China, the Chinese calendar continues to hold significant cultural importance. Drawing similarities to other ancient calendar systems, such as the Babylonian, ancient Indian and Jewish calendars, the Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar that melds the lunar month cycle and the solar year cycle.

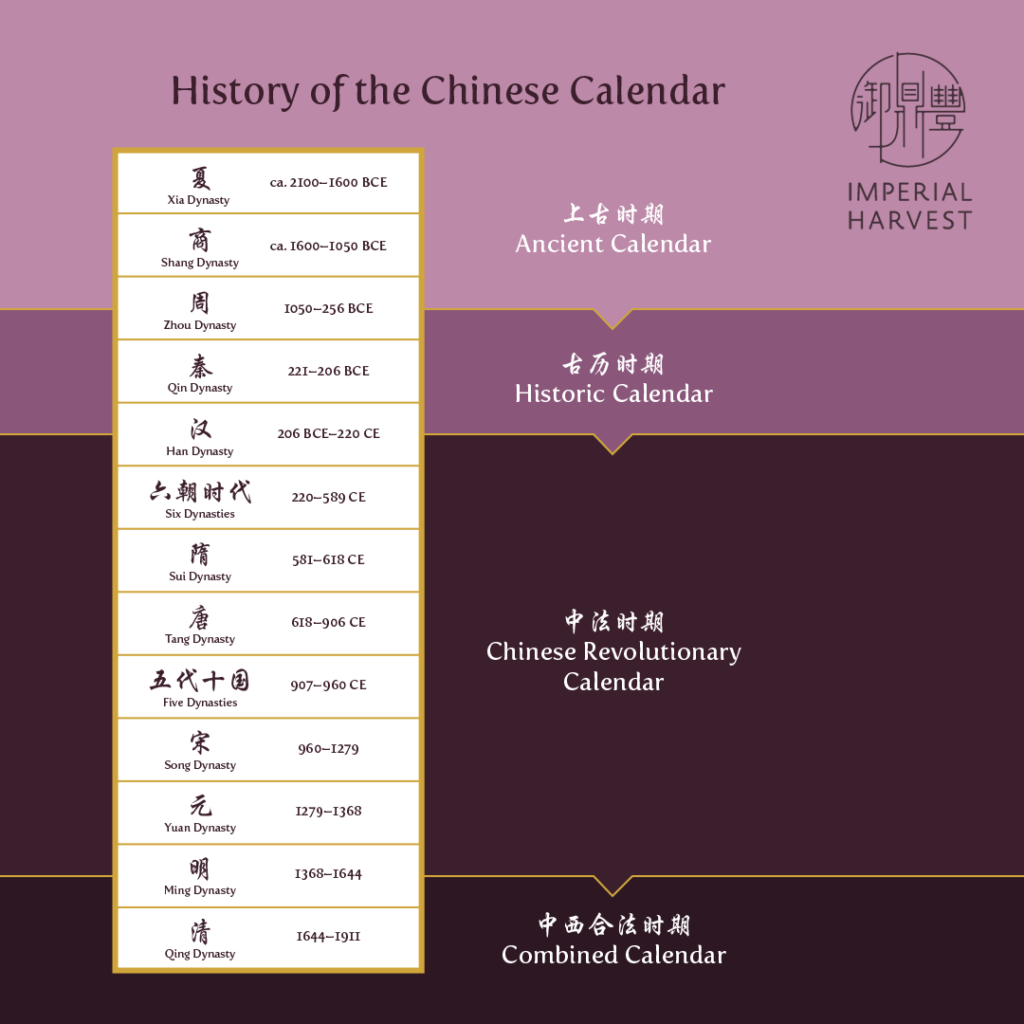

History of the Chinese Calendar

A long history underpins the Chinese calendar, dating back to the early Zhou dynasty (771 to 256 BC) when it is thought to have been first introduced. It has undergone significant development and revision since, resulting in the contemporary Chinese calendar that is recognised today. Over thousands of years, the Chinese calendar has been refined through careful observation and research of astronomical phenomena, culminating in an accurate and precise date calculation system.

The overarching developmental history of the Chinese calendar can be summarised in four major periods — The Ancient Calendar period (上古时期), the Historic Calendar period (古历时期), the Chinese Revolutionary Calendar period (中法时期) and the Combined Calendar period (中西合法时期).

| Calendar Period | Dynasties | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Calendar (上古时期) | Xia, Shang, and early Zhou dynasties (Between 2070 and 771 BC) | Astronomical observation and research laid the groundwork for the development of mature calendar systems. |

| Historic Calendar (古历时期) | Warring States period, Qin and Han dynasties (Between 476 BC and 220 AD) | Six official calendar systems were developed during this period: the Yellow Emperor Calendar (黄帝历), Zhuān Xū Calendar (颛顼历), Xia (Hsia) Calendar (夏历), Yin Calendar (殷历), Zhou Calendar (周历) and Lu Calendar (鲁历), collectively known as the "six ancient calendars". |

| Chinese Revolutionary Calendar (中法时期) | Han and Ming dynasties (Between 202 BC and 1644 AD) | This period marks the Taichu calendar reform by Emperor Wu of Han. By the end of the Ming dynasty, several calendar systems were developed and reformed, although the basic principles and models remained unchanged. |

| Combined Calendar (中西合法时期) | Ming and Qing dynasties (Between 1368 to 1912 AD) | This period refers to the end of the Ming dynasty to the beginning of the Qing dynasty. Western scientific methods and concepts were introduced with the arrival of Jesuit missionaries, and subsequent calendars were developed using a combination of Chinese methods and terminology with Western scientific concepts. |

In this article, we will explore the early development of the Chinese calendar, with a focus on the Ancient and Historical periods.

Ancient Calendar Period

The Ancient Calendar period in the history of the Chinese calendar encompasses the first documentation of calendar calculation systems that emerged during the Xia (2070 to 1600 BC), Shang (1600 to 1046 BC) and Zhou dynasties (1046 to 256 BC).

For ancient ancestors, the rational scheduling of agricultural activities was a crucial undertaking that required a sufficient understanding of the changes in nature and climate. From observations of the rising and setting of the sun, the waxing and waning of the moon, the migration of birds and the changing seasons — these periodic changes in natural phenomena gradually led people to form concepts of the years, months and days. Eventually, they looked to the stars, observing lunar phenomena as a reliable calculator for years and dates — setting the conditions for the first calendar calculation systems.

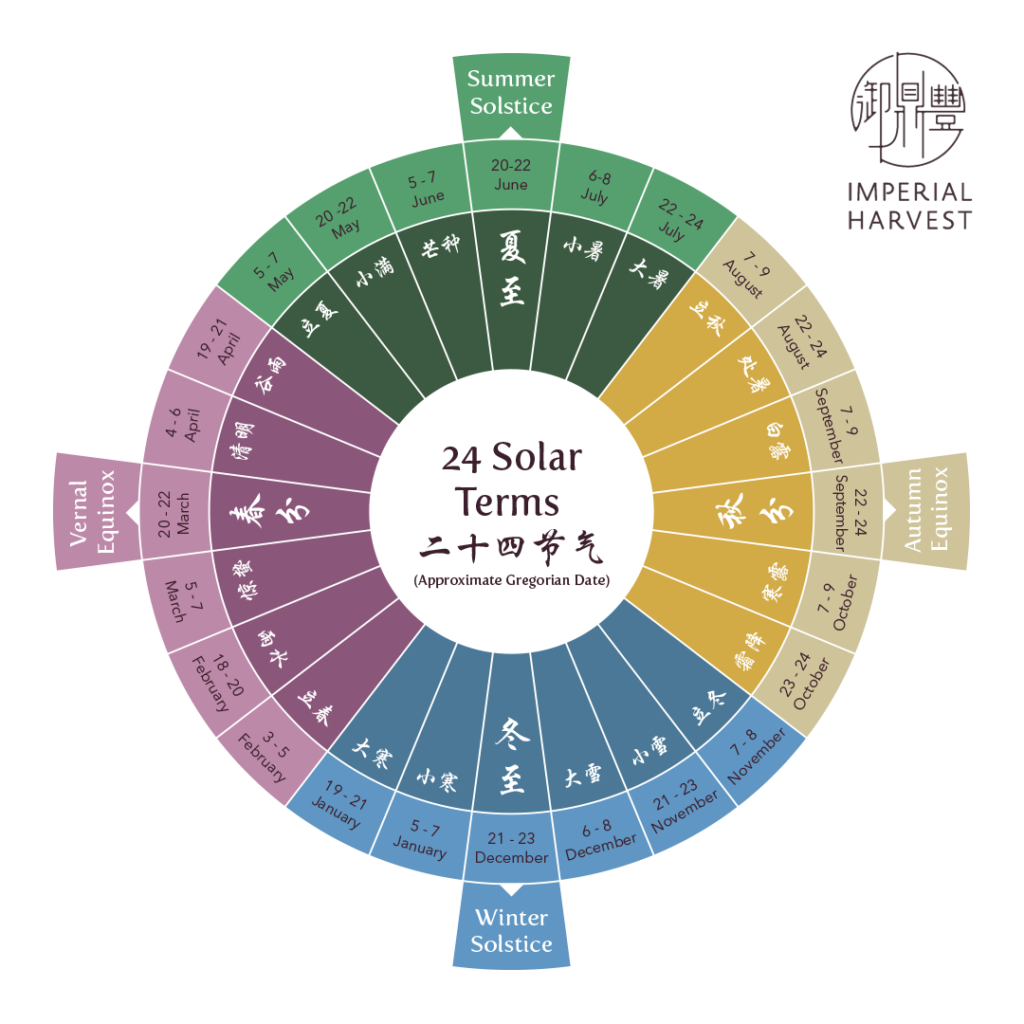

Written in the Xia dynasty, 《夏小正》(xià xiǎo zhèng) is one of the earliest surviving scientific documents and the earliest documented agricultural almanac from the ancient Chinese civilisation. This text documented the Big Dipper constellations as indicators of the different months and is believed to have the first mentions of the Winter Solstice (冬至), as well as the 24 solar terms. Oracle bones from the Yin people, an aboriginal tribe that later established the Shang dynasty (1600 to 1046 BC), first mentioned the moon’s phases in the relationship between the changing climates and the movement of the stars. These inscriptions also held the first mentions of the early lunisolar calendar calculation methods, documenting the use of the four seasons, heavenly stems and earthly branches in ancient calendar calculations.

Through archaeological inscriptions and engraved brass pots, historians were able to glean that Zhou dynasty astronomers understood concepts like the phases of the moon, and held an understanding and foundation of calendar calculation. Written records, poetry and prose from the Zhou dynasty mentioned planetary movements, such as that of the planet Venus (金星). Astronomers of this time developed their understanding of the lunar phases, discovering concepts around the “Crescent” (朏) phase of the moon — leading to an eventual confirmation and revision of the then-existing lunar calendar.

Historic Calendar Period

The Historic Calendar period saw the establishment of six main calendar calculation systems, documented during the Warring States period (476 to 221 BC), to the Qin (221 to 206 BC) and Han dynasties.

During the Warring States period, people made significant advancements in creating a consistent and reliable way to calculate the calendar. The unification of China eventually led to the development and release of mainstream calendars in different regions and provinces within the dynasty. Between 722 and 481 BC, there were countless attempts to revise the calendar, resulting in no less than 700 permutations of named months, 394 specific dates related to the heavenly stems and earthly branches, and 37 eclipses. Records from around 589 BC referenced solar eclipses (日食) and new moons (朔日) in their calculations, resulting in the acceptance of the 19 Years and 7 Leap Months (十九年七闰月) lunisolar system as the most accurate calendar calculation method to date.

The lunisolar calendar, also referred to as the farmer’s calendar (农历), and the Yin calendar (阴历), is a combination of both lunar and solar calendar calculation systems which remedies the discrepancies between both calendars, taking into account both the moon’s orbit around the earth and the earth’s orbit around the sun.

As ancient China was a primarily agricultural society, the lunisolar calendar was used as a guide for farming communities to determine the appropriate times for agricultural activities. During the Han dynasty (202 BC to 9 AD, 25 to 220 AD), the solar year was further divided into 24 solar terms (二十四节气), marking astronomical events such as equinoxes, solstices and other natural occurrences to guide farming communities in their productivity.

During this period, the《汉书·艺文志》(hàn shū yì wén zhì) — the earliest surviving literary bibliography in ancient China — documented the development and use of six primitive lunisolar calendars: Yellow Emperor Calendar (黄帝历), Zhuān Xū Calendar (颛顼历), Xia (Hsia) Calendar (夏历), Yin Calendar (殷历), Zhou Calendar (周历) and Lu Calendar (鲁历) — known as the six ancient calendars.

The Qin dynasty, after unifying China, introduced a calendar system that incorporate the concept of the Five Elements (五行). This new calendar, known as the Zhuān Xū calendar, used each element to represent the succession of emperors. Later, the Han dynasty incorporated the Zhuān Xū calendar, albeit with minor adjustments. However, the Zhuān Xū calendar had minimal impact on the country’s agricultural activities and was eventually phased out in favour of the Xia calendar, which marked the Spring Equinox as the beginning of the year.

The Xia Calendar (夏历)

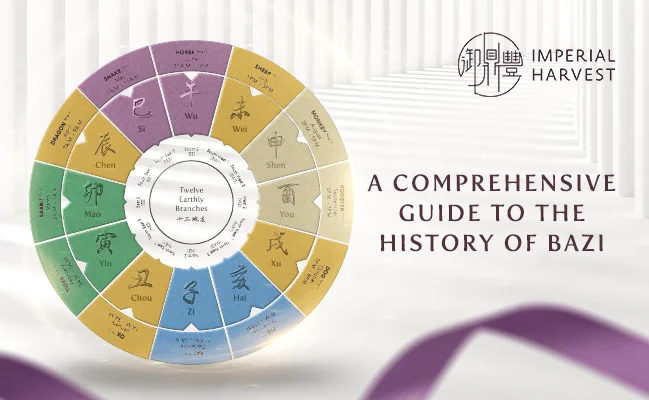

The Xia calendar, also known as the Ten Thousand Year Calendar (万年历), differs from a traditional lunar calendar, operating on a sexagenary calendar system (六十干支). The sexagenary cycle, which may be referred to as a Stem-Branch cycle, documents a 60-year calendar cycle based on the 60 combinations of Ten Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches.

Believed to have been created in the Xia dynasty, the revised Xia calendar draws many similarities with the modern-day Gregorian calendar. The Xia calendar denotes the new moon as the first day of the month, with the 15th day being the full moon. Each month in the Xia calendar follows a naming convention based on the 12 Earthly Branches and is further divided into two sub-months — known as the 24 solar terms — which reflect the changing characteristics of the seasons.

For a given date and time of birth, the Xia calendar is used to map the Bazi (八字) of an individual and determine the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches in each chart. The Xia calendar’s accuracy in the prediction of the movement of energy forces underpins a myriad of Feng Shui practices, playing a large role in aspects of Chinese geomancy, such as Xuan Kong Flying Star Feng Shui, San He Feng Shui, Bazi and auspicious date selection.

The establishment of the Chinese calendar underpins our understanding of Chinese metaphysics, its different iterations heavily influencing Imperial Feng Shui concepts of Bazi, the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches, determining auspicious periods to carry out activities. In the following article, we will delve deeper into the history of the Chinese calendar and detail its gradual evolution into the modern Chinese calendar.

Imperial Harvest’s expert consultants are always on hand to guide you on your journey and provide you with insights to help you realise your fullest potential. Book a complimentary consultation today or contact us at +65 92301640.

We are located at

For prospective clients:Imperial Harvest402 Orchard Road

Delfi Orchard #02-07/08

Singapore 238876 For existing clients:Imperial Harvest Prestige

402 Orchard Road

Delfi Orchard #03-24/25

Singapore 238876

Most Read Articles

Get to read our life changing articles and get inspired.

A Comprehensive Guide to the History of Bazi (八字)

Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins Bazi (八字) is often mistakenly assumed as the Chinese counterpart of western Astrology. The similarities between both systems lie in their utilisation of birth dates and time in their calculations, and the ability to be read from a tabulated chart. Where Astrology may take into account the positions of different […]

Imperial Harvest Consecration Ceremony

Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins At Imperial Harvest, each earthly treasure undergoes a series of consecration rites performed by Master David, before it is bestowed upon its blessed owner. Every aspect of these sacred Chinese anointing rituals is carefully examined and accurately represented in Master David’s blessings, reflecting Imperial Harvest’s deep respect for these esteemed […]

Beginner’s Guide to Bazi Reading

Estimated Reading Time: 5 mins Bazi (八字), or the Four Pillars of Destiny, is a multidisciplinary study in Imperial Feng Shui. It encompasses a well-developed set of metaphysical principles based on planetary influences, the duality of Yin and Yang, and the Five Elements. What is a Bazi Reading? Bazi is an intricate discipline within Imperial […]